IT was virtually the last question put to a deck steward, accused of murdering a passenger in her cabin on a Southampton-bound liner after she had rejected his advances and disposing her body by thrusting it through the porthole into shark-infested waters. "Are you proud of what you did on that night?"

To his eminent barrister J D Casswell KC, James Camb replied: "No, I am ashamed."

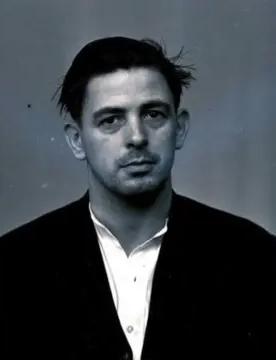

Camb, 30, spent several hours occupying the witness box at Hampshire Assizes on June 3, 1948, claiming he had panicked when she had suddenly died while they were having consensual sex and was desperate not to be caught in a compromising situation. "I put her arms through the porthole and the rest of the body followed quite easily."

His self-admitted mistake in trying to cover up her death was crucial in his defence in the most sensational trial to grip the public in post-war Britain.

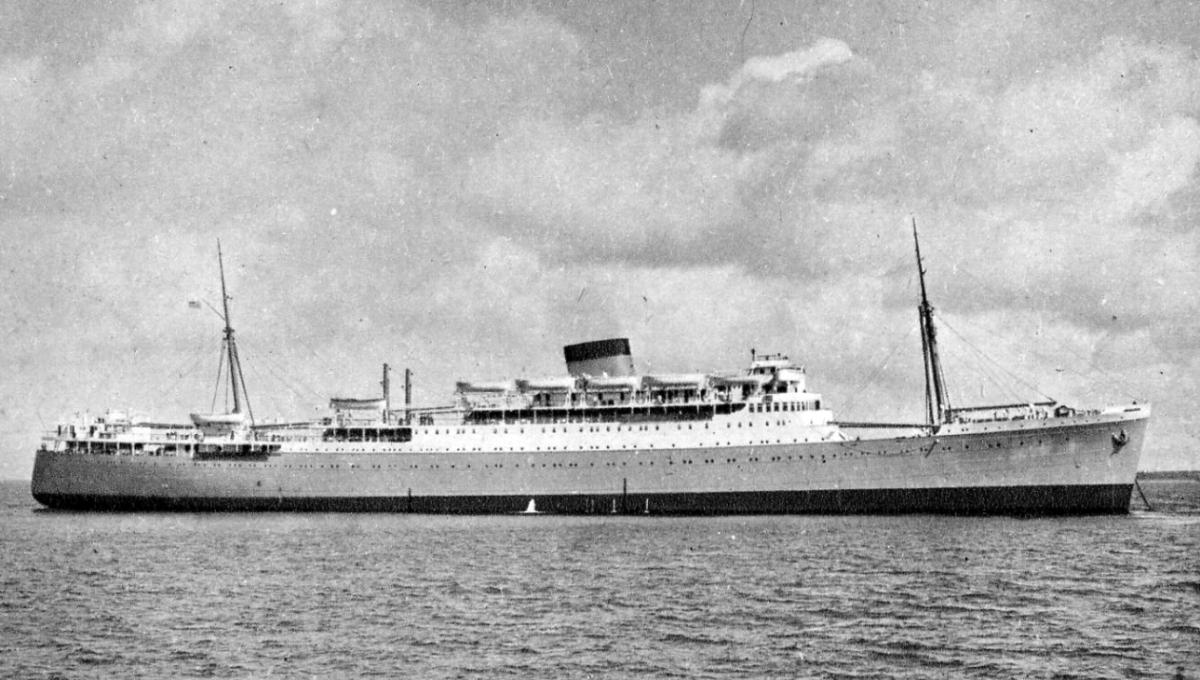

As soon as the gallery doors were opened, spectators surged forward to grab every seat in the public gallery to hear how actress 'Gay' Gibson had mysteriously disappeared from cabin 126 on the Durban Castle off the west coast of Africa.

Among the 30 plus exhibits arranged in the Great Hall were the white-enamelled bedstead and linen from her cabin. Behind it stood a replica of the porthole mounted on a plywood frame, and by its side, the door to her room. A square of cellophane on it reputedly covered marks - portions of which were indicated with paper arrows - made by Camb's hands.

Confident, even jaunty as the indictment was read out, the first-class steward's demeanour looked completely at odds with his extraordinary defence he was to mount. Though married with a child, Camb was a philandering predator who arrogantly believed women travelling alone would be beguiled by his easy going charms.

Handsome and always smartly turned out, Camb, who had served at sea for 14 years, mainly with the Union Castle Line, had acquired a reputation as a Lothario, and had already been in trouble for his association with women.

On that fateful voyage Eileen Isabella Gibson, 21, vivacious, good looking, fashionably dressed but with a largely aloof manner, caught his eye.

Professionally known as 'Gay,' she had spent six months in South Africa, appearing in stage shows, once opposite Eric Boon, the former welterweight boxing champion, but yearned for the big time of London's West End.

Camb could not resist her, even flaunting ship's regulations by being seen near her cabin on B deck. Even a ticking off from a senior officer had failed to deter him.

On October 25, 1947, the Durban Castle dropped anchor in Cowes Road after a 15-day voyage. Normally, her arrival was a routine affair but on this occasion, it had been awaited with anticipation. Press reporters and photographers gathered at the dockside as Det. Sgt. John Quinlan and Dec. Con Minden Plumley set off in a launch to embark on a complex and squalid murder case.

Gibson had spent much of the voyage alone, strangely listless and low-spirited, leaning over the rails. She was last seen alive at about 1am, leaning against a rail smoking, still wearing the black evening dress and silver shoes she had worn for that sultry night in the tropics, telling watchman James Murray it was "too hot down below" and couldn't sleep.

Initially, it was feared she had fallen overboard and the liner was turned round, making a three hours sweep of the ocean in a fruitless search, before resuming her journey. But Murray was to report that about 3am he had answered a call from her cabin and saw two lights on, indicating she had summoned both the steward and stewardess. He thought it strange and tried to enter, but his passage was blocked by Camb standing in the doorway who assured him "It's all right."

He reported his suspicions to Captain Patey and when examined, Camb was found with scratches to his wrist and shoulders. He claimed they had been self-inflicted by scratching himself because of the intense heat, but the ship's surgeon could not locate any skin disorder to have caused irritation.

The stewardess, who searched her room, felt a sense of alarm. The bedclothes were unusually disarranged and the pillows and sheets were stained with blood and saliva. Her pyjamas were also missing. On the strength of those findings, Patey radioed the Union Castle office in London who ordered him to 'Padlock and seal cabin. Disturb nothing, CID officers will come aboard at Cowes Road.'

Under questioning, Camb claimed to have been in bed and asleep before 2am, but when challenged over his reputation as a chaser of women, he admitted he had a habit of visiting them in their cabins, cynically commenting: "Some of them like us more than the passengers."

But Camb, who partly kept changing his story, eventually described how they had been enjoying sex when she suffered a fit and died. He panicked when he could not revive her and pushed her body through the porthole, displaying his cruel attitude towards Gibson by saying it made "a helluva splash."

An examination by forensic experts of the linen and the top sheets revealed traces of the blood group 'O.' Camb's was 'A.' The findings were fatal to his defence as they were consistent with death by strangulation, with features of frothing at the mouth and a discharge of blood flecks from small haemorrhages in the delicate linings of the throat, gums, lungs and nose.

Charged with murder, Camb took his place in the dock at the assizes, escorted by three warders, for the widely publicised trial conducted by Mr Justice Hilbery. Though it was revealed Gibson had suffered fainting fits, the jury of nine men and three women rejected the theory her health was so precarious she might have died from natural causes at any time, and were impressed by her mother who, despite a lengthy and severe cross-examination, stoutly defended her reputation, saying she was "one of the finest types of English womanhood, physically, mentally and morally."

Camb's improbable defence was scuppered by his inability to answer key questions. Why did he slam the door in front of a would-be helper when the ringing of the cabin bells indicated the occupant was in distress? How could he explain his statement that he had tried artificial respiration for 25 minutes, yet then had failed to call a doctor? And finally the strongest point of all - why did he dispose of her body if she had suffered a natural death?

In reality, Camb knew that her corpse constituted the most damning evidence and every instinct of self-preservation impelled him to get rid of it. His explanation he had acted in panic was hardly borne out by his calm and cool demeanour in giving evidence and it was a defence witness who ironically provided a crucial clue against him. Dr Frederick Hockin discovered the presence of dried urine - missed by the Crown's pathologist - on the linen, explaining it was common for the bladder to discharge its contents during strangulation.

Camb was doomed and jurors took a mere 45 minutes to find him guilty. Perhaps it might have been even quicker had they known he had accosted three other women on earlier trips but the evidence was deemed inadmissible.

He was sentenced to death but cheated the gallows. At the time a no-hanging bill was being discussed by Parliament and his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. An appeal against convictions was swiftly rejected.

Camb was released on licence in September, 1959, and became a waiter. He kept out of trouble for several years until he was arrested for several offences against schoolgirls. He had his licence revoked and was returned to prison.

Camb was again released in 1978 and died a year later from heart failure.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel