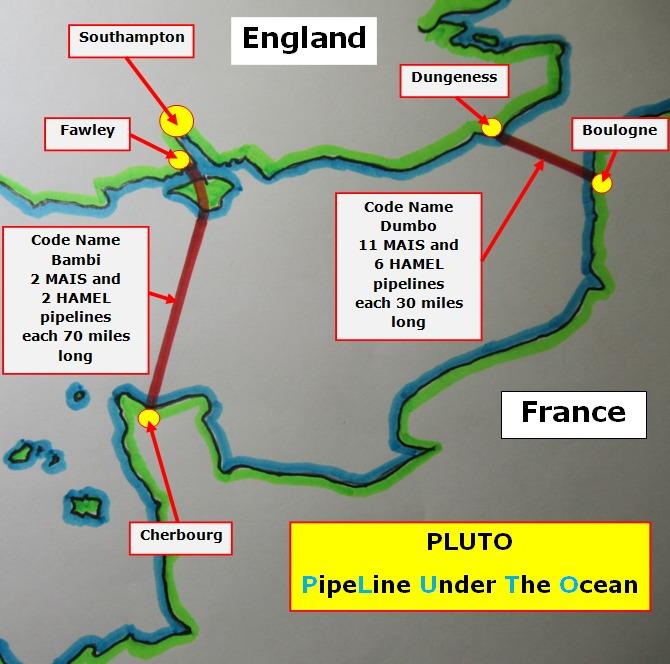

In order to support the progress of the Allied forces, PLUTO, which stands for Pipeline Under The Ocean, had an essential function in delivering 210 million gallons of fuel from England to France through an underwater pipeline.

It was early April 1942 and Geoffrey Lloyd, who served as the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Fuel, and Lord Mountbatten were observing military exercises. A question arose from the Chief of Combined Operations about potential additional support for invasion planning.

Upon being presented with the idea of laying an oil pipeline across the Channel, Lord Mountbatten, quick to see the potential, responded affirmatively: "Yes, you can lay an oil pipeline across the Channel.”

Against the scepticism of certain professionals, a solution deemed unattainable by many was envisioned by AC Hartley, the principal engineer of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, hailing from Hull.

Drawing inspiration from a challenging pumping dilemma resolved in the Iranian mountains, he devised a remarkable concept. This involved crafting a pipeline comparable to a submarine electric cable, excluding the cores and insulation, for efficient installation across the Channel in record time.

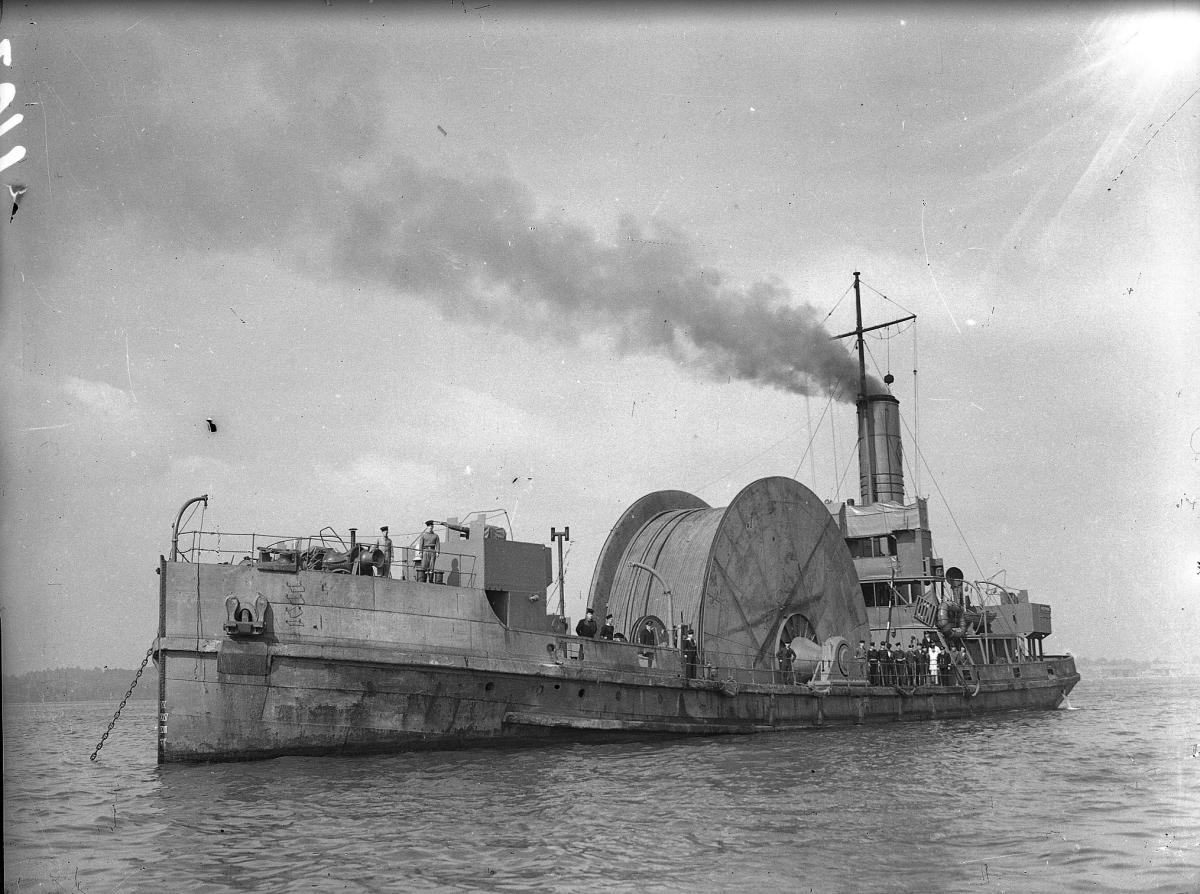

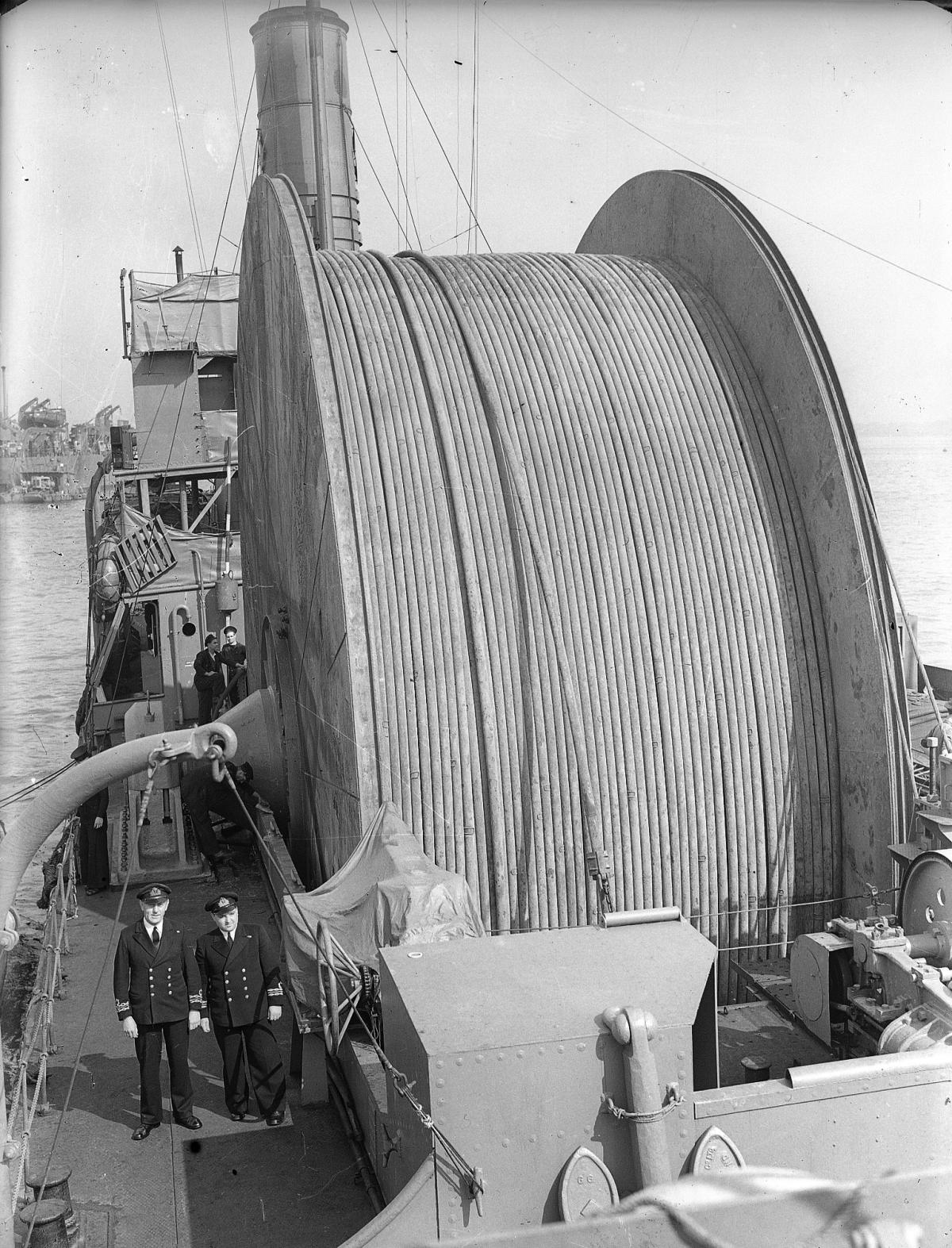

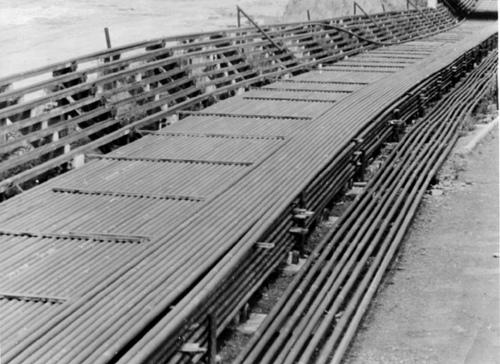

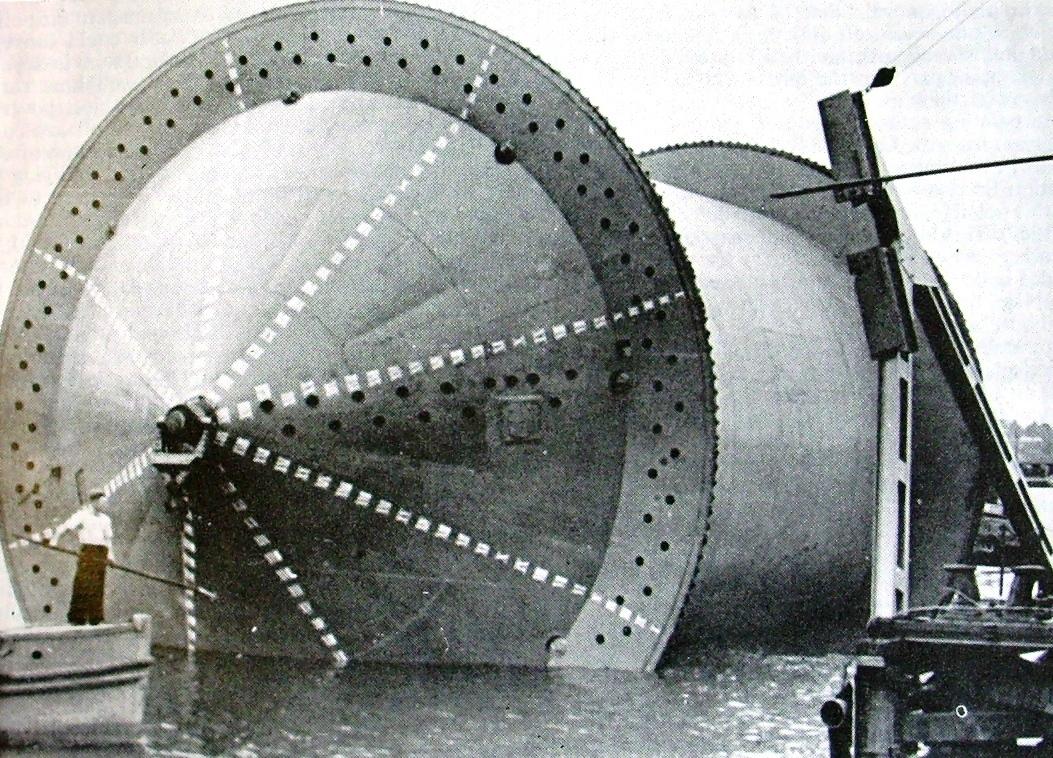

Soon after, a duo of engineers devised an ingenious strategy involving the welding of steel pipes that were coiled around a massive floating drum akin to yarn on a spool. Dubbed Conundrums in honour of the initial Royal Navy vessel that employed this method, these drums were capable of accommodating seventy miles of pipeline each.

Establishing itself as the central hub for the marathon underwater mission, Southampton emerged as the primary base for operations.

Just six weeks prior to D-Day, the headquarters of Force PLUTO were established within an ordinary house in Woolston.

Mr Lloyd and Major-General Sir Donald Banks, director general of the Petroleum Welfare Department, were known to make regular appearances.

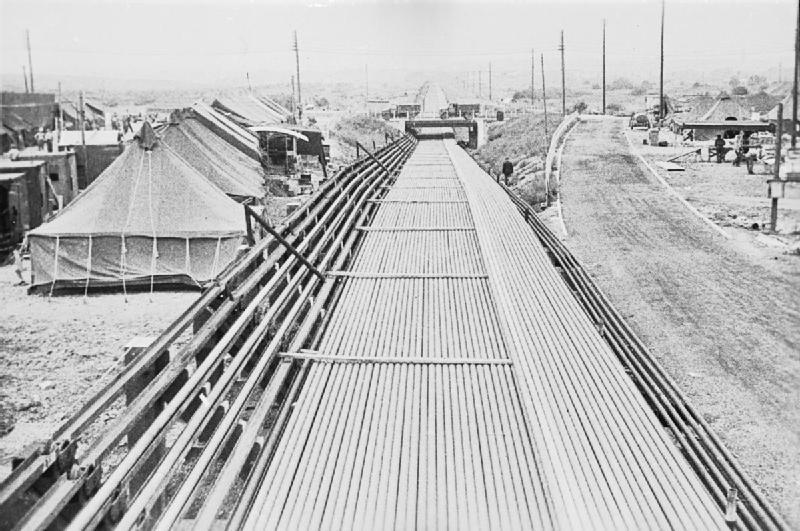

Prior to commencing the initial installation of the pipeline towards Cherbourg, approximately 20 lines were already positioned from Lepe, situated along the Solent, to the northern coast of the Isle of Wight.

These lines extended further to Sandown and Shanklin, where robust pumps were set up to serve as the core of the vital fuel distribution network.

The connection of Southampton with the pipeline persisted as the Supermarine aircraft factory suffered bombing attacks, leading to its transformation into a naval base to support the operation.

Operating under a shroud of utmost secrecy, the mission was executed with precision. In the dead of night, materials were carefully transported and concealed in various locations to evade detection by enemy air patrols.

As the momentous day of the Normandy landings dawned, the operation of PLUTO commenced, but the laying of the pipeline struggled to match the pace of the invading troops. Guided by powerful deep sea tugs, the unwinding reels moved forward gradually, restricted by slow speeds and the constraints of specific tidal conditions.

Following this, an extensive network of pipelines was established connecting Dungeness to Boulogne. However, referring to PLUTO as a single pipeline would be inaccurate. Instead, it comprised various pipelines, including those constructed with lead core armoured in steel and others made solely of steel. Together, these pipelines spanned a total distance of 770 miles.

In the aftermath of the conflict, the task of salvaging the essential pipeline presented itself as a challenging yet lucrative endeavour.

It began on September 12, 1946, when the plumbing needs of 50,000 houses were supplied from recovered PLUTO pipeline. The first major complication came when it was discovered that the pipeline had been cut at various points three miles off the cliffs of England in the interests of coastal shipping.

Despite the intricate maze of undersea paths, every thread was successfully traced. Upon retrieval aboard the Empire Taw with support from the Empire Ridley, a surprising discovery was made - a stash of 75,000 gallons of high-octane petrol. This unexpected windfall was promptly handed over to the Petroleum Board.

The British government invested approximately £3,000 per mile in developing PLUTO, but it was eventually sold for about £2,400 per mile due to inflation. Despite this, the project remained one of the most cost-effective wartime endeavours.

During its peak usage, PLUTO transported a staggering one million gallons of petrol daily across the sea to France.

Sir Winston Churchill sent a message to the unveiling ceremony of a plaque marking the place where the pipeline left Shanklin for Europe which read: "Operation PLUTO was a remarkable feat of British engineering, distinguished in its originality, pursued with tenacity and crowned by a complete success.

"This creative energy helped to win the war, but it is no less necessary in peace.

"There must be no faltering in the drive to nurture in the British people by all possible means and above all, through education, the virtues of skill and inventiveness.

“These are true characteristics of a virile nation in a technological age.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel