THE sky an infinity of blue, the water unruffled, the supreme summer's day represented the ideal opportunity to go sea fishing. Three members of the same family in one boat, several others including five young women in another, anchoring some 150 yards apart two miles offshore.

A distant ship's wisps of smoke on the horizon was all that moved but gradually it became thicker. Heading east in their direction was the Medina steamer with 200 passengers on board specifically hired for an excursion trip around the Isle Wight with a two hour stop over at Shanklin.

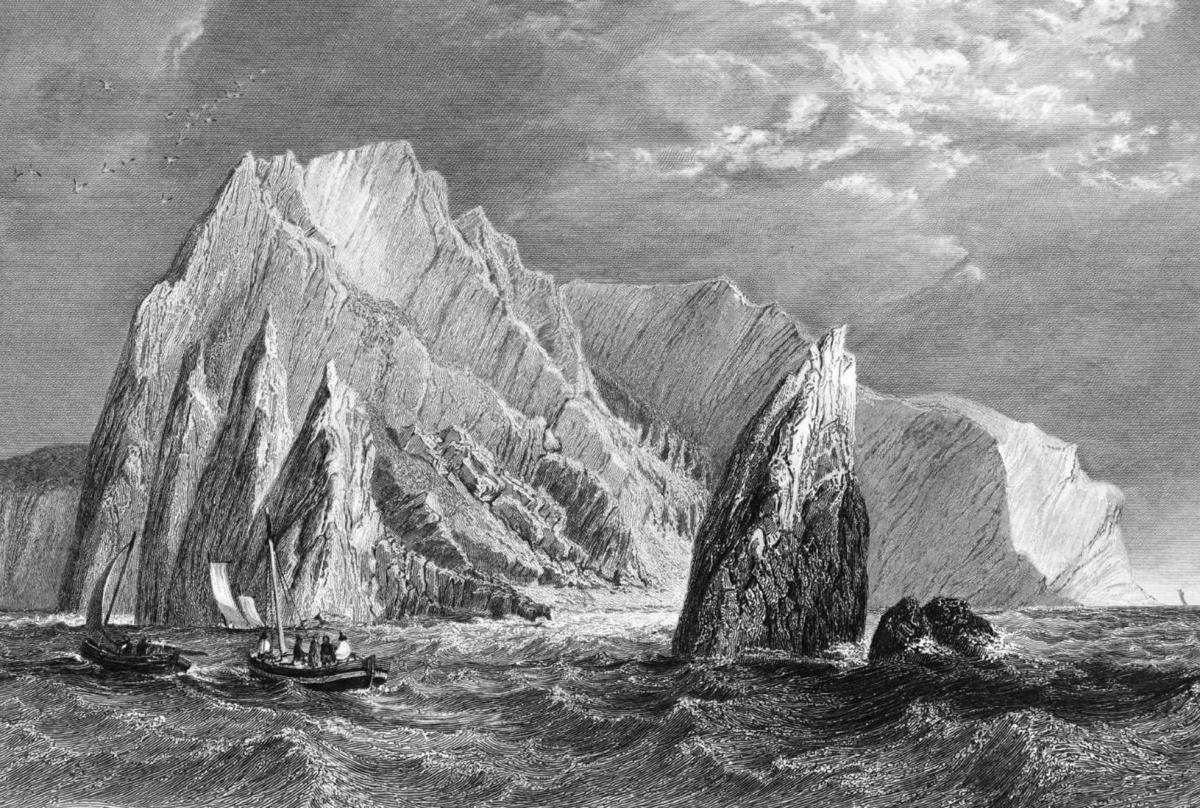

At 5pm she was first spotted off The Needles. No one initially took much notice of her approach. How could they not be seen? But slowly they realised to their horror it was not changing course and heading straight for one boat.

On impact, it was sucked under the paddle wheel. Three brothers were thrown out and drowned - William Wearn, a married father of three, George, 21, and single, and Jacob, just nine.

By a cruel twist of fate, they had perished in the same waters as their father eight years earlier when he gallantly tried to save the crew of another vessel, the Llan Romney.

David Cotton, who had known the brothers for many years, witnessed the August 8, 1853 tragedy from the other boat which was almost swamped.

"She was two miles off when we first saw her. It was a clear day and the sea was very smooth. She appeared to be coming down fast and there was nothing to put her out of sight when we first saw her. We took no particular notice of her exact course.

"When George Wearn found he was in danger, he jumped and hallooed to the steamer to bear off. The other did so also, very loud for I am deaf and I heard them. The starboard side of the steamer struck the bow of the larboard side; the boat was knocked right round and sucked under the paddle wheel.

"We picked up our stone as fast as we could and tried to save William who had been in the water for some time, and I think we should have saved him if the steamer had not backed.

"Very little time elapsed from Wearn's hallooing till the boat was run over. There was a great number of people on the steamer. I cannot say there was time after the hallooing to have turned the course of the steamer. I was present afterwards when the bodies were found, two of them were entangled in the fishing nets."

Listening intently at Hampshire Assizes on March 4 the following year was the Medina's skipper, 33-year-old David Corke accused of manslaughter. It was the prosecution's case that Corke at the time had his back to the bridge and engaged in throwing nuts from a basket to passengers below for a scramble.

Mr Poulden, for the Crown, alleged: "The captain being in his position to look out, is, by his culpable and criminal negligence, answerable for the consequences that took place."

But the defence were adamant he had been made the scapegoat and the blame lay with his crew for disobeying a crucial order.

John Light, who had been steering the Medina at nine knots an hour, told the court Corke had been on the bridge but with his back to it for about 10 minutes before the collision.

"If I had a signal, there was plenty of time to avoid a boat. I recollect a collision taking place, I heard a crush alongside. I could not see any boat before me but I could see a boat on the other side. I had my eye on the captain for a signal but received none.

"As soon as the collision took place, I heard shouting on board the steam boat but no hallooing from the boat. There was a great deal of noise in the scramble.

"When I heard the noise, I saw two poor souls go under. The engine was stopped, the vessel backed and a boat lowered but no life was saved. Boat and all had disappeared. We could that day distinguish a boat at the distance of two miles and I could have had a signal, I could have avoided the boat but no one spoke at the wheel."

James Saunders said he acted as mate but had not received any directions to take charge of the Medina, and fellow seaman William Harris was adamant he had not received any instructions from Corke as being a look-out.

"My duty was to do whatever there was do." He told the cabin boy John Bessant "to look out for bit" before going down below at Saunders's request.

"The captain was then on the bridge looking out. In going below, I went down in front of the captain when he might have seen me."

He had been there for about eight minutes when the crash happened.

"We had no regular rules for looking out but did so amongst ourselves. After the captain went below, the vessel was in no one's charge. I had no orders, nor anyone else to my knowledge. He was in charge and there was no one at bows. I considered the captain was on the look out when we went below."

So who was telling the truth?

The defence slammed the facts laid before them as a false and wicked mis-representation with the sole object of obtaining a conviction and not arriving at the truth.

"One of the whole of the three witnesses who have been examined, are the real guilty parties and it is they who ought to have been indicted, " Mr Sewell submitted.

"It has been a conspiracy on their part, from first to last, to throw the blame from their shoulders to those of their kind friend and able captain.

"How is it that not one of those 200 disinterested parties, who might have come and spoken the truth, have not been called, and the case rests on the evidence of these three miserable men who have come here to betray their master and attach to him such a fearful charge. Conscious gult was written on the face of the mate and expressed in every word he uttered."

He claimed that after the Medina had left Shanklin, he had been looking after the passengers and been engaged in other duties which by necessity distracted him from being in charge of the ship.

"The mate and the crew knew very well such was the case and it was a pretext and a falsehood to say he was in charge of the vessel. He had called upon them to take charge, and the men themselves, according to their own showing, had been at the bows and look out within five minutes of the time the accident. The captain no doubt believed them to be still there and he must be exonerated."

Though Saunders denied it, Corke's father told the court he had specifically reminded over and over again that the deck must not be cleared without two people on look out for the passengers' safety.

He stressed: "It is true there were no printed regulations but the duties of the men were well understood and being a look out was part of their duty," adding his son had to be physically restrained from jumping overboard to try and save the fishermen.

The judge, Baron Martin, directed jurors in his summing up that it was incumbent on any person whether being in charge of a boat or a car to take care for if death occurred from negligence, he must be found guilty as charged, even though he did not mean it and was sorry for it as anyone could be.

"Negligence might be very gross or very trifling. Although there might have been negligence on part of others, if a captain was negligent concurrent with theirs, he is equally guilty. It depends not on what orders were given or what was told from one to another but on what exactly occurred.

"If the statement of Light it appears at the time of the occurrence he was throwing nuts out a basket for a scramble, the question for you is whether the captain so engaged was doing his duty. If the men did not look out, it was his duty to make them.

"No doubt, he is an exceedingly clever and able man, but that is not the question."

Jurors retired for an hour before acquitting Corke, their verdict being met with great applause.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here