THERE was shame and sorrow surrounding her sinking.

One survivor appeared before local magistrates charged with theft. Less fortunate families gathered in another seeking compensation.

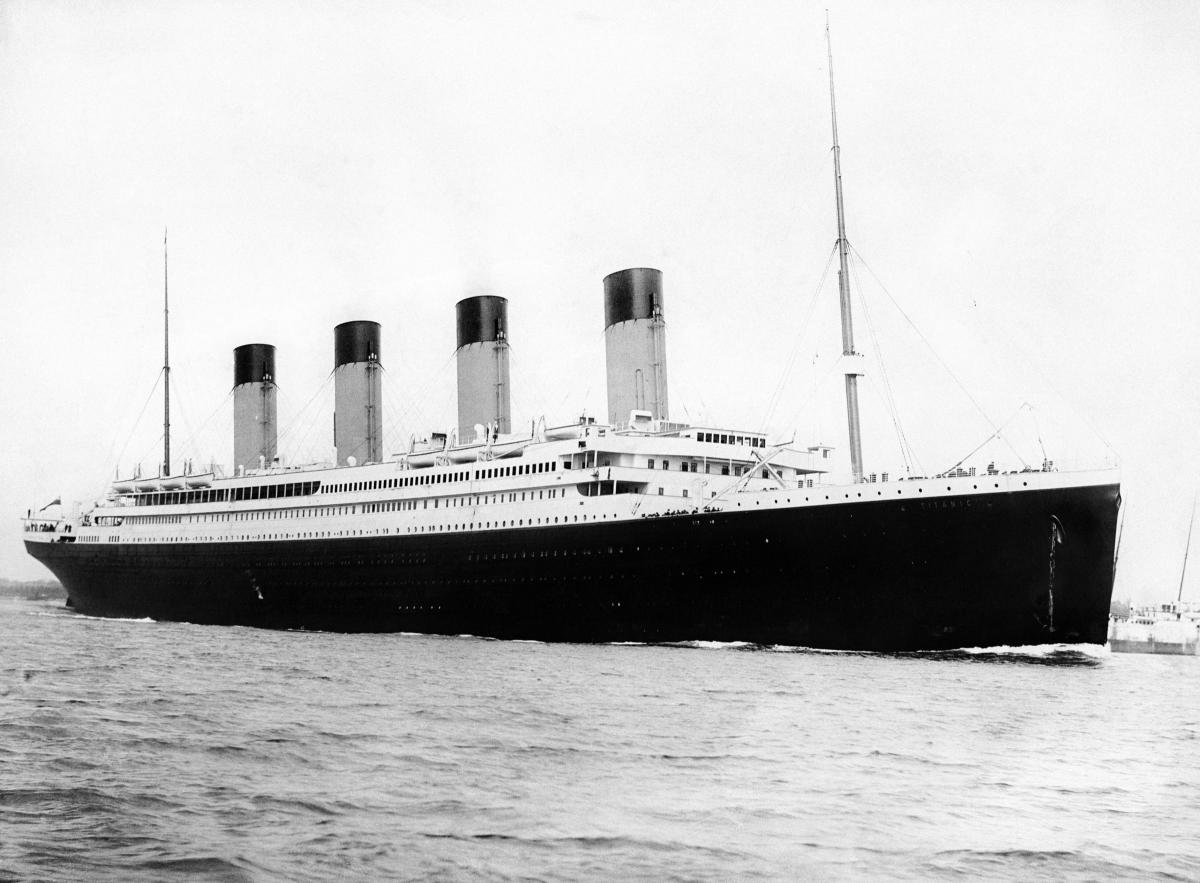

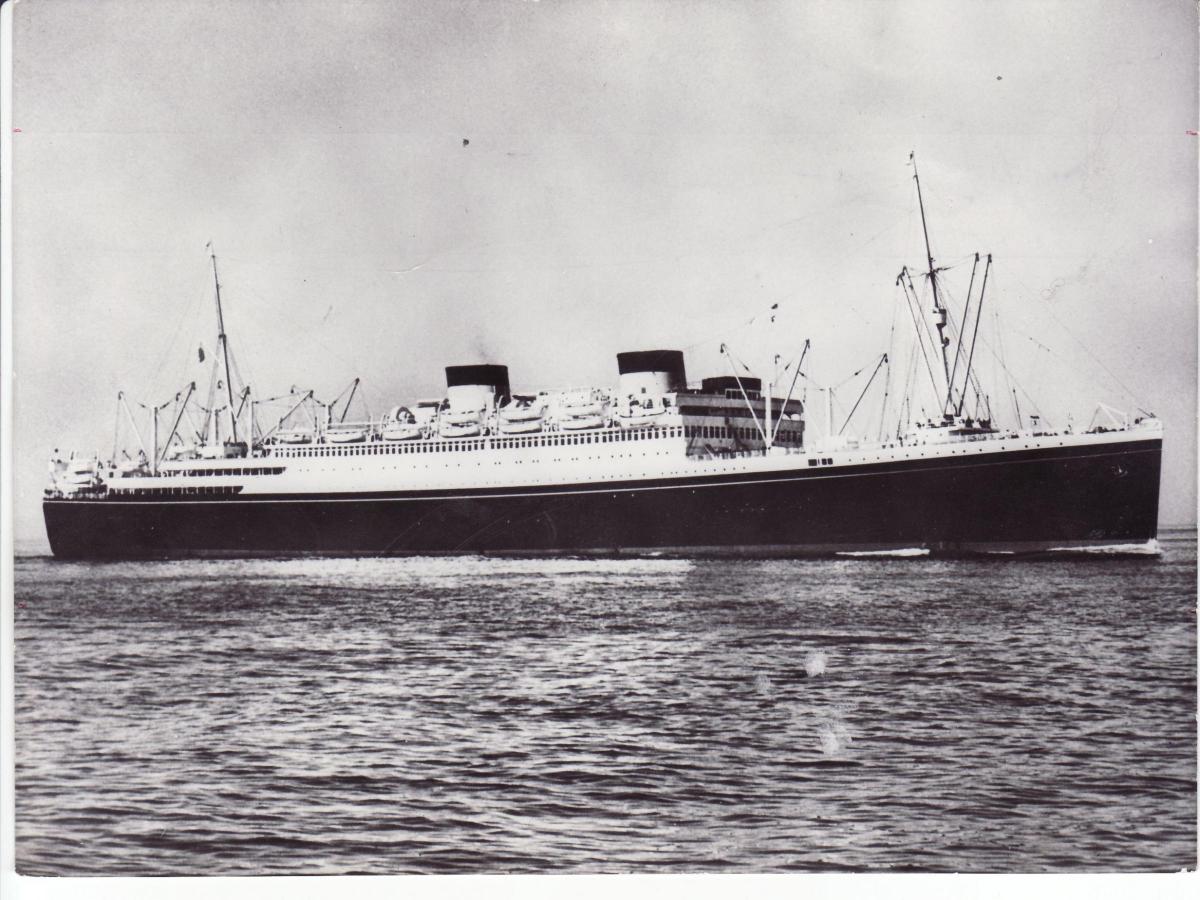

HMS Britannic was the largest of the White Star Line's Olympic class of vessels and as sister ship to the ill-fated Titanic, had been built for the burgeoning trans-atlantic passenger service.

But it was a role she was never destined to play.

Built just before the start of the First World War, she was initially requisitioned as a transport troop ship for the Gallipoli campaign but with the landings proving disastrous and casualities mounting, she was converted into a hospital ship, repainted white with large red crosses and a horizontal green stripe to illustrate her purpose to the enemy.

After completing five missions, bringing home the wounded, the Britannic left Southampton on November 16, 1916, for the Mediterranean, calling at Napes to replenish coal and water stocks. Leaving the Italian port, she was carrying 673 crew, 315 Royal Army Medical Corps and 77 nurses.

Hours later she struck an underwater mine near the island of Kea and water began pouring in through the starboard side.

Following measures taken after the Titanic's sinking, the liner's design had been modified and ordinarily the watertight doors would have enabled her to float but several portholes had been left open on the lower decks because of the intense heat and water poured through them.

The skipper, Captain Charles A Bartlett, attempted to get the Britannic beached at the island but with a heavy starboard list and the steering gear renderered useless, the liner was doomed and he quickly gave the order 'Abandon ship.'

She sank within an hour - the largest ship to founder in the war.

Violet Jessop, who had survived the Titanic's sinking, was again working as a nurse on board, describing the Britannic as "The white pride of the ocean's medical world."

She told the Press of her last few moments.

"She dipped her head a little, then a little lower and then lower. All the deck machinery fell into the sea like a child's toys. Then she took a fearful plunge, her stern rearing hundreds of feet into the air until with a final roar, she disappeared into the depths, the noise of her going resounding through the water with undreamt violence."

Miraculously only 30 people were lost.

Unlike the Titanic's passengers ordeal, the water was warm, more lifeboats were available and help from local fishermen and HMS Scourge were close.

The following April, claims were heard under the Workmen's Act at Southampton County Coiurt arising from the tragedy.

The first applicants were Joseph Phillips, a Buresledon labourer, and his wife who lost their son Chas Phillips, a trimmer. They sought £120 compensation on the gounds they were largely dependent on his earnings and rejected the sum of £60 the White Star Line as inadequate.

They detailed his income for the three years he had been with the company, mentioning that he gave his mother £1 a week while working in a local shipyard which continued while he served on a vessel running short voyagdes. Regular and larger payments were made during his time on other vessels, including the Britannic.

The court agreed with their request.

It then took the case of Percival White, also a trimmer, whose parents lived in College Street. His father, James, had also been aboard the liner but was rescued.

They sought £150 against the company's offer of £75.

Deputy Judge Lush was told he only spent four days at home at intervals of three months and banked 10s for him out of the 30s he gave them for his keep.

E F lever, who represented the White Star Line, submitted the sum paid into court was sufficient in the circumstances.

However the jdge overruled them and awarded the parents £108 with costs.

A few days later, James Baldwin, a survivor, appeared in court in ignominious circumstances - charged with theft from the Union Castle Line.

The town magistrates heard baldwin had gained a job as a stevedore and had been seen by a member of the Army Service Corps, carrying a suspicious parcel which he hid in a recess. He reported the matter to a superior officer and the police were informed.

Baldwin, in pleading not guilty, said when he saw the parcel he did not know what it was and spoke to a colleague who also did not known.He then put into the stringers of the ship.

On being convicted, Southampton's chief constable Allison confirmed Baldwin was "a native" of the town and after surviving the Britannic's loss, had been working in the docks.

Magistrates, noting he was of previous good characer, bound him over in the sum of £5.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated: 1st January 1970 12:00 am

Report this comment Cancel